12 Things to Do for Homeschool Spring Nature Study

Now I am going to give you a prescription, — for some woods medicine, — a magic dose that will cure you of blindness and deafness and clumsy-footedness, that will cause you to see things and hear things and think things in the woods that you have never thought or heard or seen in the woods before. Here is the prescription : —

Wood Chuck, M. D.,

MULLEIN HILL.

Office Hours:

5.30 a.m. until Breakfast.

Rx

No moving for one hour . . .

No talking for one hour. . .

No dreaming or thumb-twiddling the while.

Sig: The dose to be taken from the top of a stump with

a bit of sassafras bark or a nip of Indian turnip

every time you go into the woods.Wood Chuck

Dallas Lore Sharp (The Spring of the Year)

Last spring, I began a series of posts in which I shared some ideas for things to see for nature study for spring, summer, fall, and winter from Dallas Lore Sharp’s nature books. I mentioned that I have come to love these books covering the different seasons of the year. In the past, during our Morning Time, we have taken about ten minutes per week to read through whichever one was relevant to the season we were in, and it was so insightful and inspirational. They have given us a greater appreciation for nature, of course, and my kids love the personal stories and reflections he includes.

Some of my favorite parts are the “lists” he also provides. These include things to see, things to do, and things to hear in a given season, and they’re a great way of getting the whole family outdoors and actively keeping their eyes and ears open. It has also helped us to observe the natural world around us all the more closely.

Today, I’m sharing his list of ideas of things to do for your spring nature study from The Spring of the Year. I have also included links to resources that will help you through each of the items, and I have a free downloadable version at the end of the post that you can print out and bring with you, along with field guides and nature journals, during your nature excursions. Spring is the perfect time of year to get into a good habit of going on a nature walk every week, as everything is new, and there is so much to observe!

I want to add before I dive into the list that some of these items are specific to the area of the country in which Sharp lived (New England). However, you can substitute something from your area if you need to. He emphasizes in item four that you should get to know the common things of your area, and I think this is excellent advice!

For instance, an easy way to get to know the different birds that are prevalent in your area would be by hanging up bird feeders or adding a bird bath to your backyard. We also have boxes on our shed for bird nests. We started doing this back in 2015 and it has been such a fun way to be able to identify birds, but also to get to know their different personalities.

And now, on to the list!

12 Ideas for Spring Nature Study

I do not know where to begin — there are many interesting things to do this spring! But, while we ought to be interested in all of the out-of-doors, it is very necessary to select some one field, say, the birds or flowers, for special study. That would help us to decide what to do this spring.

I

If there is still room under your window, or on the clothes-pole in your yard, or in a neighboring tree, nail up another bird-house. (Get “Methods of Attracting Birds” by Gilbert H. Trafton.) [I have a post about attracting birds to your backyard as well!] If the bird-house is on a pole or post, invert a large tin pan over the end of the post and nail the house fast upon it. This will keep cats and squirrels from disturbing the birds. If the bird-house is in a tree, saw off a limb, if you can without hurting the tree, and do the same there. Cats are our birds’ worst enemies.

II

Cats! Begin in your own home and neighborhood a campaign against the cats, to reduce their number and: to educate their owners to the need of keeping them well fed and shut up in the house from early evening until after the early morning; for these are the cats’ natural hunting hours, when they do the greatest harm to the birds.

This does not mean any cruelty to the cat — no stoning, no persecution. The cat is not at fault. It is the keepers of the cats who need to be educated. Out of every hundred nests in my neighborhood the cats of two farmhouses destroy ninety-five! The state must come to the rescue of the birds by some new rigid law reducing the number of cats.

III

Speaking of birds, let me urge you to begin your watching and study early — with the first robins and bluebirds — and to select some near-by park or wood-lot or meadow to which you can go frequently. There is a good deal in getting intimately acquainted with a locality, so that you know its trees individually, its rocks, walls, fences, the very qualities of its soil. Therefore you want a small area, close at hand. Most observers make the mistake of roaming first here, then there, spending their time and observation in finding their way around, instead of upon the birds to be seen. You must get used to your paths and trees before you can see the birds that flit about them.

IV

In this haunt that you select for your observation, you must study not only the birds but the trees, and the other forms of life, and the shape of the ground (the “lay” of the land) as well, so as to know all that you see. In a letter just received from a teacher, who is also a college graduate, occurs this strange description: “My window faces a hill on which straggle brown houses among the deep green of elms or oaks or maples, I don’t know which.” Perhaps the hill is far away; but I suspect that the writer, knowing my love for the out-of-doors, wanted to give me a vivid picture, but, not knowing one tree from another, put them all in so I could make my own choice!

Learn your common trees, common flowers, common bushes, common animals, along with the birds.

V

Plant a garden, if only a pot of portulacas, and care for it, and watch it grow! Learn to dig in the soil and to love it. It is amazing how much and how many things you can grow in a box on the windowsill, or in a corner of the dooryard. There are plants for the sun and plants for the shade, plants for the wall, plants for the very cellar of your house. Get you a bit of earth and plant it, no matter how busy you are with other things this spring.

VI

There are four excursions that you should make this spring: one to a small pond in the woods; one to a deep, wild swamp; one to a wide salt marsh or fresh-water meadow; and one to the seashore — to a wild rocky or sandy shore uninhabited by man.

There are particular birds and animals as well as plants and flowers that dwell only in these haunts; besides, you will get a sight of four distinct kinds of landscape, four deep impressions of the face of nature that are altogether as good to have as the sight of four flowers or birds.

VII

Make a calendar of your spring (read “Nature’s Diary” by Francis H. Allen) — when and where you find your first bluebird, robin, oriole, etc.; when and where you find your first hepatica, arbutus, saxifrage, etc.; and, as the season goes on, when and where the doings of the various wild things take place.

VIII

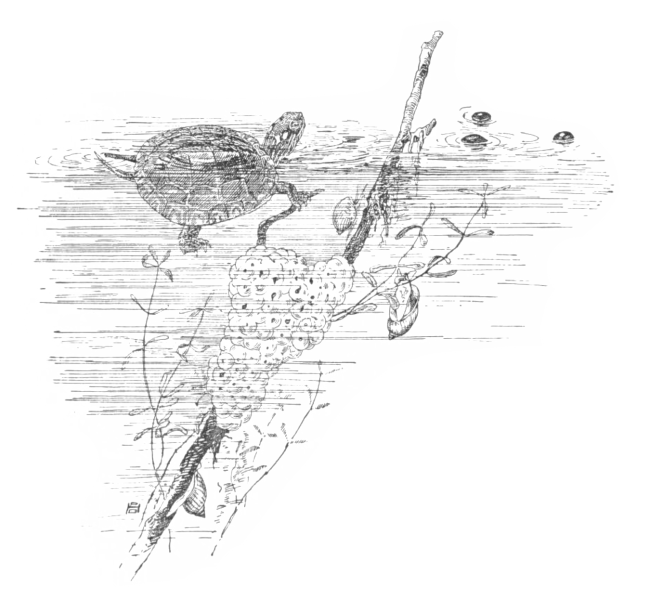

Boy or girl, you should go fishing — down to the pond or the river where you go to watch the birds. Suppose you do not catch any fish. That doesn’t matter; for you have gone out to the pond with a pole in your hands (a pole is a real thing); you have gone with the hope (hope is a real thing) of catching fish (fish are real things); and even if you catch no fish, you will be sure, as you wait for the fish to bite, to hear a belted kingfisher, or see a painted turtle, or catch the breath of the sweet leaf-buds and clustered catkins opening around the wooded pond. It is a very good thing for the young naturalist to learn to sit still. A fish-pole is a great help in learning that necessary lesson.

IX

One of the most interesting things you can do for special study is to collect some frogs’ eggs from the pond and watch them grow into tadpoles and on into frogs. There are glass vessels made particularly for such study (an ordinary glass jar will do). If you can afford a small glass aquarium, get one and with a few green waterplants put in a few minnows, a snail or two, a young turtle, water-beetles, and frogs’ eggs, and watch them grow.

X

You should get up by half past three o’clock (at the earliest streak of dawn) and go out into the new morning with the birds! You will hardly recognize the world as that in which your humdrum days (there are no such days, really) are spent! All is fresh, all is new, and the bird-chorus! “Is it possible,” you will exclaim, “that this can be the earth?”

Early morning and toward sunset are the best times of the day for bird-study. But if there was not a bird, there would be the sunrise and the sunset — the wonder of the waking, the peace of the closing, day.

XI

I am not going to tell you that you should make a collection of beetles or butterflies (you should not make a collection of birds or birds’ eggs) or of pressed flowers or of minerals or of

arrow-heads or of —anything. Because, while such a collection is of great interest and of real value in teaching you names and things, still there are better ways of studying living nature. For instance, I had rather have you tame a hop-toad, feed him, watch him evening after evening all summer, than make any sort of dead or dried or pressed collection of anything. Live things are better than those things dead. Better know one live toad under your doorstep than bottle up in alcohol all the reptiles of your state.

XII

Finally you should remember that kindliness and patience and close watching are the keys to the out-of-doors; that only sympathy and gentleness and quiet are welcome in the fields and woods. What, then, ought I to say that you should do finally?